A government software manufacturer dedicated to furthering the responsible application of today’s wealth of information, GovPilot has published blog posts exploring both the light and dark sides of Big Data. A new development in the Golden State Killer case raises questions about the area in between.

A History of Violence

On a February evening in 1978, 21-year-old, Brian Maggiore and his wife, Katie, 20, took their poodle, Thumper, for his nightly walk by their Rancho Cordova, California apartment. Perhaps the young couple was lost in conversation or maybe they actively sought a change of scenery, but Brian and Katie deviated from their usual route and took a left on Malaga Way. Neither could have predicted the consequences of this seemingly trivial choice.

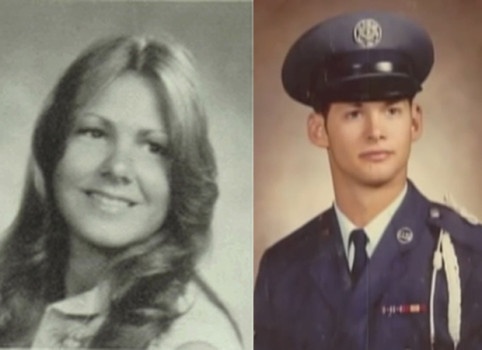

Katie and Brian Maggiore were the first couple murdered by the Golden State Killer.

Katie and Brian Maggiore were the first couple murdered by the Golden State Killer.

It was on Malaga Way that Brian and Katie had a violent encounter with a man that ended with him pulling-out an “unknown caliber” gun and opening fire. The couple was rushed to a nearby hospital, where they were both pronounced dead upon arrival. Their beloved Thumper was later found shivering in a neighbor’s pool. The Maggiore murders were the first in a string of 12 that occured in a similar fashion throughout California over the next eight years.

Piecing Together a Puzzling Case

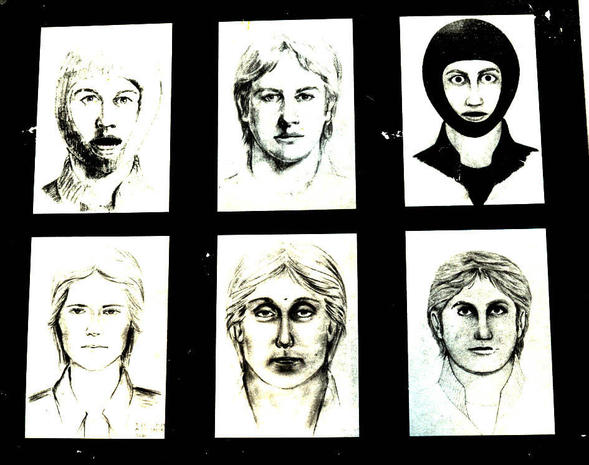

More than 50 rapes and 100 burglaries were reported in California during this same stretch of time. Though these crimes had commonalities, including a suspect that fit the same physical description (young, Caucasian, male), they sometimes occurred hundreds of miles apart— a detail that stymied investigators.The distance and lack of DNA profiling technology made it unlikely that law enforcement would ever find the man responsible.

12 murders, 50 rapes and 100 burglaries were thought to be committed by the same California man, but the distance of the crime scenes and lack of DNA profiling technology made it unlikely that the Golden State Killer, as he came to be known, would ever be found.

It wasn’t until 1996— a decade after the Golden State Killer’s last murder— that DNA profiling technology had advanced to the point that a sample from the victim’s body could be matched to DNA from several California rape and murder cases from the same era.

The breakthrough reignited media interest in the case. Affected jurisdictions banded together with the FBI to solicit tips from the public and offer reward money. Despite the best efforts of the task force, no suspect matched the DNA profile, as the man had never been caught for a subsequent crime where his DNA would have been collected.

A Long-Awaited Lead

In the 40 plus years that the Golden State Killer was at large, the world changed dramatically. One major difference between the 1970s, when the killer began his spree, and today are the ways in which data is aggregated, analyzed and applied.

A prime example is how mainstream genealogy has become in recent years. Thousands of customers share DNA with online genealogy services, like Ancestry, 23andMe and Family Tree DNA in the hopes of discovering their roots, their likelihood of carrying/developing genetic diseases and reconnecting with long lost family members. In March 2017, the Eastern District of California subpoenad Family Tree DNA parent company, Gene by Gene, for “limited information” regarding a particular profile that law enforcement believed to be linked to the Golden State Killer’s DNA.

DNA expert, Paul Holes, led the investigation. With the information provided by Gene by Gene, Holes was able to identify the killer’s great-great-great grandparents, who lived in the early 1800s. Branch by painstaking branch, Holes and his team created about 25 family trees containing thousands of relatives down to the present day.

One fork led to a 72-year-old retiree living in Sacramento’s Citrus Heights district. The man was a disgraced cop, which Holes thought could explain why he may have been able to evade capture for over four decades. Holes was even more intrigued when he discovered that the man had purchased guns during two bursts of activity by the killer.

In mid-April 2018, officers scooped up an item discarded by the man that contained his DNA and tested the genetic material against the killer’s. It was a match. Joseph James DeAngelo was arrested on April 24th.

Genealogical information provided by database, Gene by Gene, led investigators to 72-year-old, Joseph James DeAngelo.

An Answer Raises New Questions

Upon DeAngelo’s arrest, Katie Maggiore’s brother, Keith Smith, expressed relief. “He’s had all of the control the entire time. And now we have that control.”

While the public is happy to see the Golden State Killer locked away, not everyone approves of the methods police used to track him. According to the New York Times, the detectives on the Golden State Killer case uploaded the suspect’s DNA sample to GEDMatch, a database of DNA aggregated from online genealogy websites. GEDMatch would have prompted them to check a box online certifying that the DNA was their own, belonged to someone for whom they were legal guardians, or that they had “obtained authorization” to upload the sample.

Investigators obviously didn’t have D’Angelo’s permission, but Erin Murphy, a law professor at New York University, maintains that they may not have needed it. “Under current constitutional law, the government has a tremendous amount of discretion in how to use crime-scene evidence. DNA abandoned at the scene of a crime basically has no legal protection.”

Though law enforcement may have the legal right to leverage genealogical data in a criminal investigation, some wonder if it is ethically sound. As University of California Davis Law Professor Elizabeth Joh warns, “Do you realize, for example, that when you upload your DNA, you’re potentially becoming a genetic informant on the rest of your family? […] And then if that’s the case, what if you’re the person who didn’t personally upload the DNA, but you discover that your family member has done that?”

Companies that offer DNA testing have sought to reassure their customers that they will not easily hand information over to law enforcement. As documented in 23andMe’s transparency report, as of Dec. 15, 2017, the company had received five requests from United States government agencies for information on customers, but had complied with none. However, the companies also concede that they may be forced to obey valid subpoenas, court orders, or search warrants for customer information. GEDmatch’s website includes this warning, “DNA and Genealogical research, by its very nature, requires the sharing of information. Because of that, users participating in this site should expect that their information will be shared with other users.”

The Golden State Killer was arrested in a gray area that lies between public and private, information and action. It is one of many examples of legal and ethical quandaries bound to arise in this age of Big Data. Follow each one on GovPilot’s blog.