If you make it to age 125, how will you spend your days? Will you keep 9:30 AM to 6:00 PM office hours? Rally for a cause you’re passionate about? At 125, non-profit organization, the Municipal Art Society (MAS) of New York does all of this and then some.

Join GovPilot as we look at the ways in which MAS has literally and figuratively shaped New York as well as the organization’s vision for the future.

The Manhattan Project

In 1893, Manhattan, as we know it today, was just beginning to take form. Health regulations, workers’ rights and many of the priveleges and protections we enjoy were decades away from serious consideration, but the freshly founded MAS was ahead of the curve. Concerned with Manhattan residents’ quality of life, members financed the creation of murals on the sides of public buildings and sculptures at city parks.

As Manhattan scaled, so did the organization’s ambitions. In the years that followed, MAS advocated for the construction of public housing to accomodate the millions of immigrants pouring into New York City, the passing of the Zoning Resolution of 1916 and the 1930 development of Rockefeller Center, among other notable actions. Whereas MAS played an integral role in the genesis of modern Manhattan, it is best known for protecting a piece of its past.

In the early 20th century, MAS advocated for the construction of public housing to accomodate the millions of immigrants pouring into New York City.

The Historical Society Makes History

The story of MAS’ most well-known achievement begins on the heels of what many consider to be its biggest blunder. In 1961, in response to decades of dwindling ticket sales and structural decay, the Pennsylvania Railroad announced plans to demolish (what has come to be known as) the original Penn Station, built in 1910. The announcement sparked outrage amongst a small, but stalwart group of architects, who balked at the idea of the grand, Classical station being demolished and replaced with modern office buildings, a new Madison Square Garden and a new station below.

The architects looked to MAS to champion their cause, but were disappointed when then-chairman, Harmon Goldstone, explained the organization’s stance in a letter published in Progressive Architecture magazine’s October 1961 issue. Goldstone writes, “Is the proposed new building, for its own purpose, in its own idiom, going to be as inspiring a design as [the architectural firm that designed the original Penn Station] McKim, Mead & White’s? There is no reason why it cannot be.” In the end, the cries from the picket line of architects parked in front of the original Penn Station were drowned-out by voices, like Goldstone’s. The old terminal was torn down in 1963.

The controversy over the demolition of iconic old Penn Station paved the way for the passage of New York’s Landmarks Preservation Law—an act that MAS and its influential allies fought to apply to the protection of another Manhattan train station.

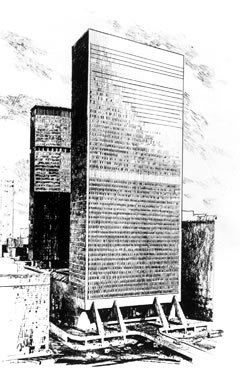

In 1975, the court voided Grand Central Terminal’s New York landmark designation, greenlighting a redesign that would render the station another box-shaped mass in Manhattan’s storied skyline. Opened in 1913, Grand Central Terminal boasts the Classical architectural elements and historical significance that had inspired people to protest the demolition of the original Penn Station thirteen years prior. Perhaps it was seeing the modernist nightmare that replaced the original Penn Station, perhaps it was new leadership or maybe it was the recent memory of public backlash. Most likely, it was a combination of all three that sprung MAS into action to protect Grand Central Terminal.

The strength of MAS’ cause was no doubt bolstered by its bevy of high profile supporters. Former first lady, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, TV personality, Dick Cavett, beauty queen, Bess Meyerson, and others joined MAS in its quest to save Grand Central terminal from demolition and return the station to its former glory.

A sketch of the proposed redesign of Grand Central Terminal.

The mission was a success. MAS and company managed to save the station from demolition and raise funds for a major rennovation—which did as much to restore the station as it did MAS’ reputation.

Those who protested the slated demolition of Grand Central terminal often referenced the contrsoversial demolition of the original Penn Station 13 years prior.

Those who protested the slated demolition of Grand Central terminal often referenced the contrsoversial demolition of the original Penn Station 13 years prior.

Planned Work

MAS continues its efforts to “mobilize diverse allies to protect New York’s legay spaces, encourage thoughtful planning and urban design and foster inclusive neighborhoods across the five boroughs.” Current initiatives include protecting New York’s 80 acre network of public plazas and arcades, safeguarding zoning restrictions to preserve the boundaries of Manhattan’s Garment District and helping New Yorkers become stronger advocates for their neighborhoods. After all, there’s no time for rest when watching over the city that never sleeps.

GovPilot salutes MAS for its 125 year commitment to community progress—one we share and forward with our government software. We are excited to see what the future holds and promise to cover noteworthy developments (structural and otherwise) on our blog.